I Hate Poetry but I Love TV(or, K.D. @ 4–oh/4–reel)

The callow seeming title of this, Kim Dorland’s eighth solo exhibition with Angell Gallery, is a bluff. In his Toronto studio in August, Kim told me that he likes both poetry and TV. Its false braggadocio rings with second-wave nostalgia for the receding prior nostalgia of an early incarnation of the artist who habitually slipped into the indications of a former adolescent cockiness. Today he nestles the intimate, ephemeral now-ness of time as he watches his children and family (and self) live through instances that occur and vanish in a flicker.

Yet, while the title is not literally true, it is otherwise apropos. Dorland chooses not to paint with poetic embroidery or temerity. His imagery is prosaically undisguised; his vocabulary reflexively automatic, journalistic, matter-of-fact; his palette ALLCAPS attention-grabbing, vivid, even lurid; and his mark making emphatic with punctuation as much as description. That punctuation inflects…no, directs the amassments of colour on his canvases and it crucially articulates the stories that emerge from his pictures. Dorland’s claimed affinity to television speaks to the day-by-day mesmerisation of far and near exotica (and the commonplace) denatured and re-naturalized by the keyed-up glow of the household screen.Home plays a bit role in these latest paintings, all from 2014, insofar as it is only one of many settings for family life, its events, activities and passages. Because, it seems, the artist’s observations of his family might occur anywhere or anytime. His profoundly immersive, psychic recognition of the simultaneous presence, difference and absence of those closest to heart powerfully relocates and envelopes the benchmark portraits of his self-possession (versus their self-possession) in an array of locations. So, even when he is away from home, it feels local and proximate to a specific moment. An image snatched during an evening run, High Park, connotes what Dorland acknowledges as “a melancholic year [as an artist] that doesn’t reflect [his] point of view with respect to his family or his responsibilities”—a not uncommon refrain from a forty-year-old man.

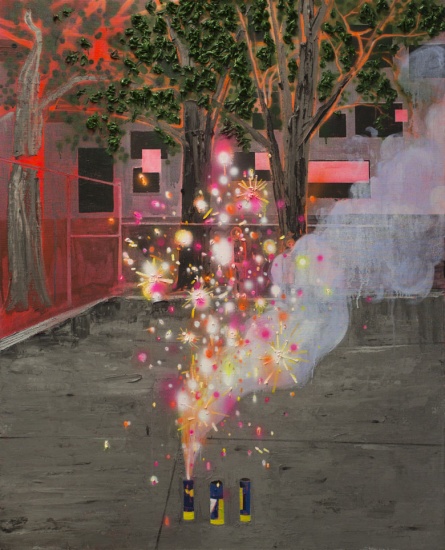

Digital photography is an essential tool and reference for Dorland’s ongoing image archive of daily life passing into the subjects for his paintings. It naturally fits such a prolific and prodigiously gifted artist. Pictorial prowess and facility such as Dorland’s allows for the gradual, uncontrived seeping of meaning into one’s work. For all its outrageous stylizations and exaggerations of colour and form, Dorland’s paintings remain essentially objective. Therefore he does not prefigure or predestine his attitude to their content. By constant return to themes and real views, not only does he gauge the changes of his subjects, but also notices his variances in perceptive and emotional state. Sometimes key incidents shimmer in through placid and routine surroundings, such as a hazy and distant police car parked in the centre of the aforementioned High Park. Similarly, the efflorescent sparkle and fuming of Fireworks almost completely occlude a pair of humble witnesses meekly standing against the back fence of the concrete yard, Dorland’s sons, Seymour, eight, and Thomson, five.

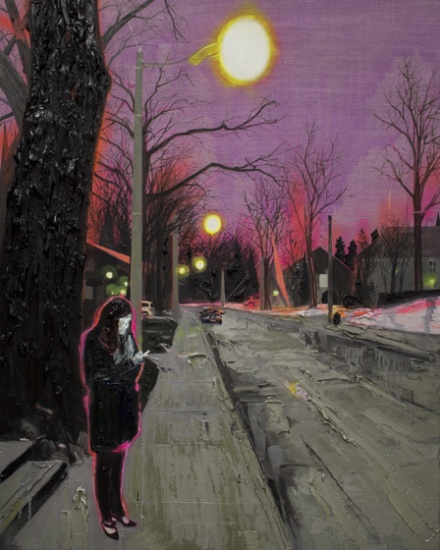

The compositional reference to cell phone images gains consonant ordinariness in that such devices are ubiquitous, possessed by his subjects too. His wife, Lori, is plausibly aglow as she looks to her screen in the winter evening of After the Party. Crystalline flares and a voltaic underpainting refer to how Dorland recorded the scene. In Bleeding Heart, the small screen isolates and rebalances the image, deepening and thickening a garden around Seymour into jungle, where he sits oblivious to its ominous foliage, inspecting a blossom gently with his fingertips, not absorbed in a video game as it might initially appear.

March Break and Don’t Give Up are two of Dorland’s most effectively pared-down paintings, each with an abstracted, horizontal banding that yields classic, stacked, rectangular order. The elegant simplicity of each is a feat of artistic restraint, nerve and hard-won experience. In March Break, Seymour stretches upward in preparation for a dive into a pool, with concentration, determination, perhaps some trepidation. His taut body and arms are mimicked above by the upright trunks and limbs of bare trees, and contrasted by an unbelievably limber and confident graffiti tag on the grey wall behind. His face, as is standard for Dorland’s figurative treatments, is a slathered impasto of relief-map planes in oil paint which still conveys a specific portraiture. This technique conveys the vertical musculature of his son’s body and also the horizontal surface plane and concealed depth of the water, of which the human body is largely composed. Don’t Give Up, by contrast, is utterly unpopulated. It depicts the fenced-in tennis courts found in Toronto’s Trinity Bellwoods Park. The chain-link has been meticulously stenciled and sprayed, an extruded screen through which appear side-by-side court lines, posts and nets, at once substance and mirage. The foreground is a clover-pocked lawn. Above the fence line, an orange sky churns with latent energy. A bedraggled message, woven into the fence links with ribbon, is the tattered remnant of youthful spontaneity, long since departed. Each painting renders depth ambiguously, treated in distinct zones of colour and technique that are monolithic and gradated at the same time, conjuring the mists or mystery of the imminent future.

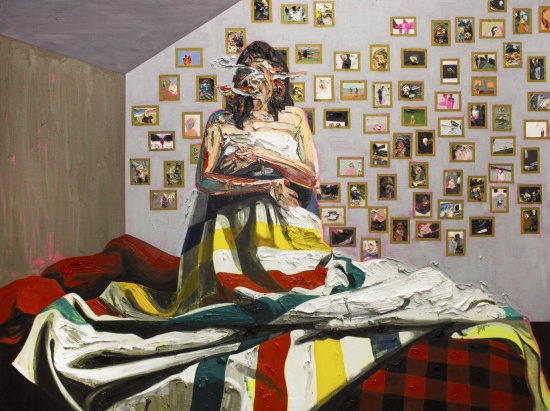

The crowning painting of a glorious show is a portrait of his muse and most frequent subject, Lori. She poses in Bay Blanket #3, as so often, in the nude, however wrapped in a recognizable wool blanket of the Hudson’s Bay Company that she clasps to her breasts and resplendently spreads down her kneeling figure and across the top of the couple’s bed. The painterly treatment of the blanket makes a transition from the thickly-painted flesh and defacement into impasto folds of heavy cloth, especially so around Lori’s torso and gently easing out to reveal some of the textile weave of the canvas on which the paint is brushed, with the signature green/red/yellow/black stripes running up and down or forward and back according to the blanket’s crumpled tumble. The bed is strewn with other rustic red/black patterns of quilting and tossed red pillows beneath her. On the wall behind Lori is a galaxy of framed family photographs, hung with a celebratory disregard for regulated order. Dorland renders each of these photos, so similar to, perhaps identical with, the sources for so many of his paintings, with tender attention to its individual distinction, its specific reference and instance in the artist’s life. He can’t help himself. He strives to keep up with evanescent life by constantly resetting and starting over.Ben PortisSeptember 2014

Artist’s biography

I Hate Poetry, but I Love TV is Kim Dorland’s first solo exhibition of new work in Toronto since the milestone success of You Are Here: Kim Dorland and the Return of Painting, at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario (October 2013 to January 2014). That exhibition, in which his paintings, many created during a residency at the McMichael, were shown alongside those of iconic Canadian landscape painters such as Tom Thomson, David Milne, Emily Carr and members of the Group of Seven, was covered in a national story in Macleans and subsequently lauded in reviews by the Toronto Star and the Globe andMail. In addition, in December, the Globe and Mail named Kim Dorland 2013 Artist of the Year. In Spring 2013, Canadian Art ran a feature profile on Dorland and, in Winter 2014, Border Crossings published an in-depth interview with the artist by Robert Enright. Kim Dorland: Homecoming, an early-career survey mounted in his native Alberta, opens at Contemporary Calgary on October 16 and runs through January 18, 2015. On October 3, Kim Dorland, an 184-page monograph is available from Figure 1 Publishing, with an introduction by Jeffrey Spalding, artistic director and chief curator of Contemporary Calgary, an essay by Katerina Atanassova, chief curator of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, and an expanded, updated version of Robert Enright’s interview. Internationally, Dorland’s art is on view this fall in Peahead, a group exhibition at Franklin Parrasch Gallery, New York, which runs until October 11. In 2015, he will be given in a solo exhibition at MCA Denver, Colorado.

Kim Dorland was born in Wainwright, Alberta in 1974. Dorland received his BFA from the Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design, Vancouver, and received his MFA from York University, Toronto. He has exhibited globally, including shows in Milan, New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, receiving reviews in the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times. Dorland’s art is in numerous prestigious public and private collections in Canada and abroad, including the Bank of Montreal; Beth Rudin DeWoody Collection; Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas, Austin; Eileen S. Kaminsky Family Foundation, New York; Glenbow Museum, Calgary; Montreal Museum of Fine Arts; Musée d’art contemporain, Montréal; Neumann Family Collection, New York; Oppenheimer Collection, Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Kansas; Royal Bank of Canada; and Sander Collection, Berlin. Dorland works in Toronto, where he lives with his wife Lori and their two sons, Seymour and Thomson.Author’s biographyBen Portis is a curator and critic in Toronto. He was formerly the curator of the MacLaren Art Centre, Barrie, Ontario and an assistant curator at the Art Gallery of Ontario. His writings have appeared frequently in such publications as Canadian Art, Border Crossings, C Magazine, Hunter and Cook and The Dance Current, as well as numerous exhibition catalogues.

Essay by Ben Portis