Oknertep, www.dailyserving.com

October 15, 2008

Tim Roda

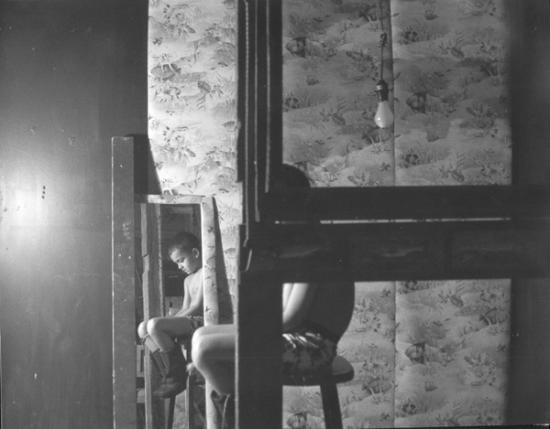

Tim Roda's exhibition, Family Album, opened on October 2nd, 2008 at the fresh San Francisco gallery, Bear Ridgway Exhibitions. Roda and his family could be called a collaborative, since the creative process involves the whole family's participation. Roda creates intricate sets (often on-the-spot) including--just to name a few--found objects, costumes and carpentry materials. Roda then invites his family into his newly fashioned space where the scenes are created--which he documents closely with a 35mm camera. Roda captures out of the ordinary moments that draw influence from his past family life. His photo development process is also unique in that he pays little attention to the exacting tasks of typical photo development--he burns, dodges, and cuts down at his own accord evoking a blurry, pixilated, and "unfinished" feel to his photographs.

Educated in ceramics, Roda earned his MFA from the University of Washington and his BFA from Pennsylvania State University. Roda has exhibited widely throughout the United States, Canada and Europe. He and his family are currently living and working in Italy on a Fulbright scholarship. DailyServing's Arden Sherman, had a chance to speak with him about his current exhibition, his working process, and what's next to come.

DailyServing: I understand that you have had a friendship with Kent Baer and Eli Ridgway of Baer Ridgway Exhibitions (BRX) for some time now. Can you tell us a little bit about the process that went into the preparation and into the actualization of your Family Album exhibition?

Tim Roda: I started working at Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle a few years ago. Both Eli and Kent worked there. We got to know each other on a more professional level. I have worked with a handful of galleries, some really organized and some really horrible. I know how Kent and Eli work and I had no doubts about getting involved with them. Even though they are a young gallery, I know their working style--they are very organized. Kent and Eli are really smart guys and I think they will go a long way. Hopefully we can have another show next year.

DS: You have used the title, Family Album, for other shows as well as the title, Family Matters. How did you select the works for this show?

TR: There are close to 150 works in Family Album, so I used the same title, though each show is different. When deciding which works go into a show, it comes down to a negotiation between artist and dealer. For a show I did in Germany, I used tape and wallpaper, creating more of an installation. Eli, Kent [of BRX] and I were into agreement about which works went into the show. The way I work is by taste and aesthetic, trial and error. I have never really made work that fits together as a whole; they are mostly all individual photographs.

DS: You create elaborate sets made out of found objects, tape, clay, and scrap building materials. Do you conceptualize these scenes before they are conceived or does the process occur organically? And does your son help with the ideas?

TR: Sometimes both. Usually the first thing I will do is start painting a white wall or cover it with wallpaper, a process that usually lasts all day. Allison brings my sons in the evening and I tell her what I am looking for--when she sees it, she snaps the picture. We work really well together. She understands me and we are on the same field of thought. Ethan's role has definitely changed, we started making photographs when he was four and now he is ten and much more aware of what is going on. A lot of the scenes come from constructed memory and family experiences... a lot of it stems from my past.

DS: Through the father-son relationship, which you document in your photographs, and your father and grandfather's inherent influence on you, do you think that you are taking--for lack of a better word--a decidedly masculine approach to documenting your time with your son? And what place do women occupy in your work, either as subjects or as viewers?

TR: My work is domestic. I think there is a gay following of my work. The gay community seems to relate to it. I think this would be a good question for a woman. I play a lot with domestic situations and I sometimes wear dresses. My father was a "tough guy" and a "hard man", so sometimes I poke fun at that. Oftentimes, in America, men do not participate in domestic activities, but my grandfather who was Italian was always in the kitchen. For me cooking is one of my favorite things to do, my wife is busy going to school for her doctorate so I have to pull the weight at home. Allison and I are 100% half and half. Right now, she is going for doctorate and when I was going through school, she took care of the house. I guess I do not address women so much in the photographs because I do not know so much about them or about being one.

DS: Plaid is an aspect of your work, in the show at BRX, and additionally referenced in the introductory essay of the exhibition catalogue by David Hunt. You created a wallpaper collage of xeroxed plaids and stripes in the gallery. Can you elaborate on your motives behind this installation? What sort of symbolism does plaid have for you?

TR: I think, for me, plaid means layers and process. I find David Hunt to be sort of plaid himself. I had to read it like six times to comprehend it! Lighting, wallpaper, fabrics, my installations need to have layers to be interesting. I am a very process oriented person. I have had traditional shows in the white-box setting and others that are more installation based--in order to show more of the process demonstrated in my working style and my photo process. I find it a whole lot easier to understand my work when the viewer can see the rolls of paper or the loose paper that I have Xeroxed and taped to the wall. When my son and wife arrive after installation is complete, it adds a whole life to the sets that I create. I started in ceramics in school and then one day took a photo of my son sitting next to it, the whole thing sort of started there.

DS: Why are most of your photos in the BRX show untitled?

TR: Titles let people off the hook. People try to come up with their own meanings based on a title. They are numbered in chronological order so, in a sense, there is a story being told. Plus I do not think I am very good at titles, so I do not want to force it. I find that people are quick to associate a title with other works and other artists. I am aware of certain artists but they do not necessarily influence that particular work or body. In school, I looked at a lot of other artists, but I think I get kind of annoyed because I do not want to be classified with them.

DS: I noticed a baby appearing in a few of your photographs. Is that your son or daughter?

TR: That is my son Rocco; he is eleven months old. This past summer we spent a residency in Spain. It was the first time we worked and lived in the same space. It was a cool experience because there was no difference between art and family or home and studio. I have an artist friend from Montana, and he was always conflicted because he wanted to go home to his family but he felt deeply inspired to keep working in the studio. My son, Ethan is also very exposed to contemporary art and artists. He sees people making work, which is totally different from what we are doing, and then we ask him about what he sees. He has a hard time connecting art class at school and the studio work of us or other professional artists. The way schools are set up, the kids only really learn traditional elementary tools.

DS: I wanted to congratulate you on receiving the Fulbright scholarship. What an honor. I understand that you will be moving to Italy to work on your project. Can you tell us what you will be working on and what we should look forward to in the future?

TR: Actually this was my third time applying for the Fulbright. Its pretty simple process, you write a proposal and they either accept it or deny it. Mine was a little tricky. I want to investigate the domestic side of Italy, which sounds pretty great to most people--cooking and hanging out in the home. I think finally my contacts and my work brought me over the top and showed them that it was not just a great vacation. I will be going to Rome and giving lectures and then we will head South go live in Pentidatillo, the village where my grandfather grew up. I am interested to see his life, his struggles, his friends, and his home. My family will join me of course-this is a very familial experience. We are all very connected to this project, we work tightly, meeting great people, traveling and being together.

Then we will head to Northern Italy where I am going to work with Eva Brioschi, who is the curator for the Gaia Collection (Collezione La Gaia). I am excited about getting to understand differences between North and South Italy and their subsequent rivalry. If you look on an Italian map, we are from just north of Melito, and no further south than there. Northern Italians are nice to us because we are American-Italian but if we were Southern Italians it would be a different story. Another Fulbright recipient told me not to decide too much before I get there. So we will see. I am confident that my work will organically evolve once I am over there and meeting people and working.

www.dailyserving.com

Posted by Oknertep at 6:44 AM